One of the most common knee injuries is an anterior cruciate ligament sprain/tear in athletes who participate in sports like soccer, and basketball. If your anterior cruciate ligament injured, you may require surgery to regain full function of your knee depending on several other factors

Understanding the Knee Joint and Anterior Cruciate Ligament

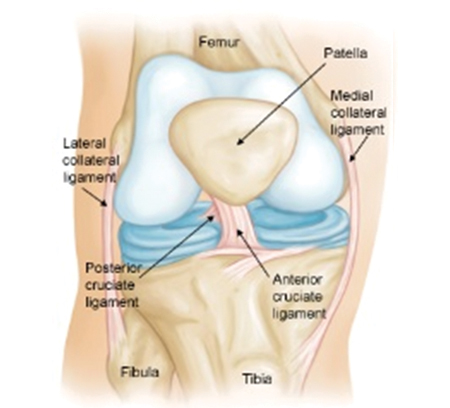

The knee is one of the strongest joint in your body. It is made up of the lower end of thighbone, the upper end of the shinbone, and the patella or the kneecap. The ends of these bones where they touch each other are covered with a smooth covering called articular cartilage. This covering protects and cushions the bones as the knee moves through the entire range of motion. The knee also contains two wedge-shaped shock absorbing gel pads called meniscus between your thighbone and shinbone. These tough and rubbery gel pads help cushion the joint and keep it stable. The knee joint also contains a thin lining of fluid secreting tissue called the synovial membrane which releases fluid that lubricates the cartilage and reduces friction. Bones are connected to one another by ligaments. There are four primary ligaments in your knee. They act like strong ropes to hold the bones together and keep your knee stable.

Types of Knee Ligaments

- Collateral Ligaments - These are found on the sides of your knee. The medial collateral ligament is on the inside and the lateral collateral ligament is on the outside. They control the sideways motion of your knee and brace it against unusual movement.

- Cruciate Ligaments - These are found inside your knee joint. They cross each other to form an "X" with the anterior cruciate ligament in front and the posterior cruciate ligament in back. The cruciate ligaments control the back and forth motion of your knee.

What is an Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injury?

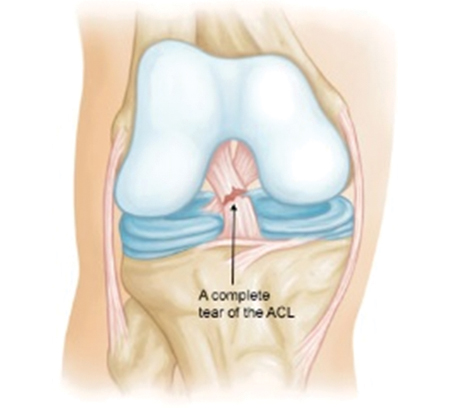

About half of all injuries to the anterior cruciate ligament occur along with damage to other structures in the knee, such as articular cartilage, meniscus, or other ligaments. Injured ligaments are considered "sprains" and are graded on a severity scale.

- Grade 1 Sprain - The ligament has been slightly stretched, but is still able to help keep the knee joint stable.

- Grade 2 Sprain- The ligament has been stretched to the point where it becomes loose. This is often referred to as a partial tear of the ligament.

- Grade 3 Sprain- The ligament has been split into two pieces and the knee joint is unstable.

Causes

- Changing direction rapidly

- Stopping suddenly or direct injury to the knee

- Slowing down while running/Landing from a jump incorrectly

Symptoms

- Pain/Swelling/Tenderness - within 24 hours

- Popping noise at the time of injury

- Loss of full range of motion

- Discomfort while walking/feeling of knee giving way

Imaging Tests

- X-rays/Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan

Treatment

Nonsurgical Treatment - A torn ACL will not heal without surgery but nonsurgical treatment may be effective for patients who are elderly or have a very low activity level and if overall stability of the knee is intact.

- Bracing - Your doctor may recommend a brace to protect your knee from instability. To further protect your knee, you may be given crutches to keep you from putting weight on your leg.

- Physiotherapy - As the swelling goes down, a careful rehabilitation program is started. Specific exercises will restore function to your knee and strengthen the leg muscles that support it.

Surgical Treatment

To surgically repair the ACL and restore knee stability, the ligament must be reconstructed. Your doctor will replace your torn ligament with a tissue graft which acts as a scaffolding for a new ligament to grow on. Grafts are taken from the hamstring tendons or the patellar tendon or rarely the quadriceps tendon. Because the regrowth takes time, it may be six months or more before an athlete can return to sports after surgery.

Rehabilitation

Rehabilitation plays a vital role in getting you back to your daily activities. A physiotherapy program will help you regain knee strength and motion. If you have surgery, physiotherapy first focuses on returning motion to the joint and surrounding muscles. This is followed by a strengthening program designed to protect the new ligament. This strengthening gradually increases the stress across the ligament. The final phase of rehabilitation is aimed at a functional return tailored for the athlete's sport.